"It doesn't matter whether the cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice" – Deng Xiaoping1

Deng Xiaoping is often considered the architect of modern China, having advocated a pragmatic

approach to economic development and embraced the free-market system of western

economies. However, many of the principles he endorsed have seemingly been turned on their

heads in the past few months and markets have begun to question whether the economic

system born out of Deng’s reforms in the late 1970s is about to change for good

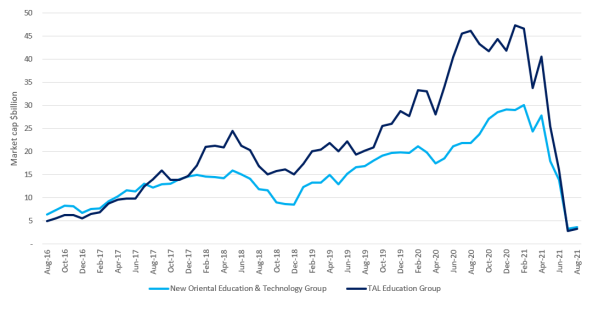

The catalyst for such concerns stem from regulatory action around China’s after-school

education companies, which had been stock market darlings, propelled by strong demand from

parents looking to get their children ahead in a very competitive education system. However, this

was recently brought to an abrupt halt as new regulation effectively made the sector non-profit.

This shrunk the addressable market for these companies from $100 billion to $25 billion2, wiping

billions off the market caps of education companies such as New Oriental and TAL Education

(Figure 1). While there have been regulatory rumblings in the sector for years, the move to non-profit was a worst case scenario that few investors had been anticipating.

Figure 1: After-school education companies (market cap, $billion)

Source: Bloomberg, as at 13 August 2021.

As the dust settles, the for-profit ban in education companies may one day be considered a watershed moment in China’s market history, and in the context of other regulatory changes facing the country’s big tech companies may be the clearest signal of intent so far of the move to

a different type of economic growth model. The prioritisation of quality rather than quantity of

growth has become increasingly important to the Chinese government, and one metric it wants

to address is the rise in social inequality, especially in the three areas of deepest concern to the

middle class: education, housing and healthcare. Highly profitable private, after-school education

companies, at which families spent 7%-9% of their household incomes in 20173, are unlikely to

be looked upon favourably under this new regime. How the cat catches the mouse is important now, not just the fact that it can catch it.

China: Innovate then regulate

Europe: Regulate then not innovate

US: Innovate then not regulate4

Europe: Regulate then not innovate

US: Innovate then not regulate4

At the same time, new regulation has also been the source of market volatility for China’s big

tech giants. Companies such as Alibaba and Tencent have been at the forefront of China’s new

economy for the past decade, spearheading the digitisation of the country’s economy with

technology ecosystems to challenge those of the leading US tech peers. Successful innovation

and exponential growth meant that, at the February peak, internet companies made up nearly

half of the MSCI China index.5

China has a history of letting industries experiment in early stages to help supercharge growth

and regulating after the fact as challenges emerge. It is now the turn of the tech stocks. Many of

the challenges regulators are seeking to tackle are the same as those facing US companies –

antitrust, data security and workers‘ rights. The difference being regulation is easier to implement

in China, and the absence of long, drawn-out rounds of consultation can make moves appear

sudden and rash. Despite growing regulation, it is important not to mix regulatory action with that

which caused the sell-off in education companies. In the case of big tech, it is highly likely the

Chinese government realises it actually needs for-profit companies to achieve another of its

policy objectives: that of greater technological self-sufficiency, an objective that has become ever more urgent since former US president Trump began his technology-focused China

containment policies in 2018. Beijing still wants tech companies to thrive, but more in ways that

meets its policy objectives.

"Crossing the river by feeling the stones"6

This takes us on to the market impact of these moves, with many participants asking if the new

policy regime makes China uninvestable? It could be argued that it is too early to make such a

concrete conclusion. Recent murmurings from government officials suggest a continued

commitment to market-based principles, with extreme for-profit bans likely to be limited to the

education sector. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to expect continued policy action in other areas

as regulators attempt to interpret and implement the government’s new focus on technological

self-sufficiency, decarbonisation and reducing social inequality.

Once again, the Chinese economy is evolving, and companies that are in areas under scrutiny

will need to change their business models. Most will emerge on the other side of the river, but it

is uncertain what type of earnings profile these companies will have in the next three to five

years. With such uncertainty affecting more than 40% of China’s equity market, the multiples

investors are willing to pay for Chinese stocks will be lower. As a result, we have exited all our

positions in Tencent, having held the stock for many years.

We must not forget, however, that China is the second largest economy in the world and growth

opportunities remain, even as the economic regime evolves. Some of our portfolio companies,

which are listed elsewhere, have significant exposure to China and we remain optimistic about

their growth prospects, especially where revenues are aligned to new policy objectives. For

example, China’s plans to decarbonise will be a likely boon for electric vehicle manufacturers,

and in turn as a supplier our holding TE Connectivity, which derives a fifth of its revenues from

the country. Similarly, the flip side of the government’s ban on after-school tutoring has been the

announcement of new policies to promote greater participation in sports, which should benefit

another of our holdings, Adidas, for which China accounts for a quarter of sales.

More opportunities will present themselves with time, but we prefer to wait until the policy picture

becomes clearer – we have not yet fully crossed the river.