What will it take to decarbonise in time?

Carbon pricing: an essential tool to achieving net zero

1. Carbon taxes are a relatively easy fiscal policy instrument to implement. They set a direct price on carbon by defining a tax rate based on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions or the carbon content of fossil fuels. With carbon taxes, the carbon price is fixed and there is no overall emissions cap, which means the exact overall emissions reduction will be implied by the carbon pricing.

However, there is often limited flexibility with carbon taxes since polluters can’t pay other companies to reduce emissions when it is cheaper to do so. As countries are increasing the level of their commitments to net zero, they are also increasing carbon taxes to help meet these objectives. For example, Norway plans to more than triple its national tax on CO2 emissions to $237/ton by 2030, while Canada plans to increase its national carbon tax more than five-fold from C$30 to C$170/ton by 2030.

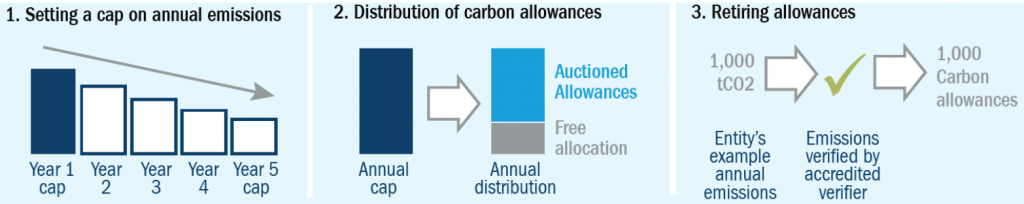

2. Carbon compliance markets are based on a cap-and-trade model where a cap is set on total emissions permitted and reduced over time. A regulator allocates or sells allowances up to the limit set by the cap. Every year entities must retire enough allowances to cover all their emissions.

A penalty mechanism is usually embedded in the event of noncompliance. Carbon prices are marketbased – entities with low emissions can sell surplus allowances to larger emitters, and the other way around. In our view, carbon compliance markets are the most effective framework for incentivising and realising emissions reductions (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Carbon compliance practical functioning

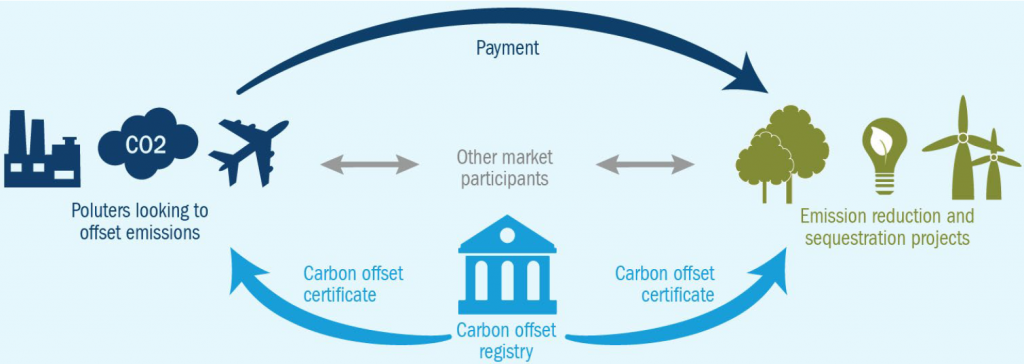

3. Voluntary carbon markets, or carbon offsets, present companies with an opportunity to address emissions they are unable to eliminate. These rest on the concept of companies being able to negate, or offset, the amount of emissions they release. An offset is created by directing funding to projects that reduce, avoid or remove CO2 emissions from the atmosphere (Figure 2). The carbon price is marketbased and depends on the supply of and demand for offsets.

Carbon offset projects include naturebased solutions like reforestation and afforestation, renewable energy and waste disposal. The outcomes need to be measurable, verified and proved effective. One big drawback of carbon offsets is that the market is fragmented and complex with a variety of different registries and methodologies. There is also a lack of standards, which presents the risk of “greenwashing” (ie, providing false or misleading information regarding the extent to which a product/ company is environmentally sound). For this reason, carbon offsets are not currently considered to be a rigorous option or replacement for other more comprehensive emissions reduction solutions. Mark Carney’s recently launched Task Force for Voluntary Carbon Markets initiative is trying to set standards on this market to contribute to the process of decarbonisation.

Figure 2: Carbon markets practical functioning

The current landscape of carbon markets

European Union

China

California

A framework for analysing the impact of high carbon prices

Pass through ability. We analyse the ability of a company to pass on higher carbon costs to customers, which could be a very important mitigating factor. There are companies for which carbon costs behave like a commodity, including utilities and chemicals such as steel and cement. These companies can fully pass the higher cost through to their end customers. So, despite being high-carbon-intensive sectors, higher carbon prices could have a moderate impact in the overall earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation (EBITDA).

Decarbonisation options. We assess how easily and costly it could be for a company within a specific sector to reduce carbon emissions, thereby offsetting the impact of higher carbon prices. For example, utilities have the potential to reduce emissions through renewables, which would reduce the sensitivity of this sector to higher carbon prices. Other sectors like aviation or chemicals rely on clean technologies that are still in development and/or not commercially available, such as sustainable fuels and hydrogen. Transition to net-zero emissions for these sectors could take longer, leaving them vulnerable to the impact of higher carbon prices.