With questions over how or if Nord Stream 1 will re-open this week, we look at Europe’s reliance on Russian imports, what this means for the market now and in the coming winter, and what Germany in particular could do about it.

What has happened? Russia reduced gas flows to Germany through the Nord Stream 1 pipeline, the key gas supply route into Germany, by 60% in June 1 – reportedly due to a turbine being held up by sanctions in Canada. At the same time, there has been no increase of flows in an alternative pipeline to make up the shortfall, as would have happened before the Ukraine invasion. While the turbine is now reportedly en route to Gazprom, Nord Stream 1 has been shut since 11 July for scheduled maintenance and is due to reopen on 21 July 2.

Why are we worried? There are fears Russia may either delay the resumption of gas flows, shut down flows altogether, or only resume flows at 40% (or lower) of normal levels. If Nord Stream 1 remains shut, Germany’s target filling rates for gas storage – 80% by 1 October and 90% by 1 November – will not be reached and there will not be enough gas this winter without demand curtailment. The consequences are severe, including a disruption of industrial production and the ripple effect through various supply chains globally. Germany will need to trigger a Level 3 Emergency Warning (see below), whereby the state takes over distribution of gas and imposes severe demand management.

How important is gas? Europe needs Russia to meet its energy demand. The EU imports nearly 60% of its total energy needs, with particularly high dependency on crude oil and gas. Nearly 30% of Europe’s energy consumption is from gas, 90% of which was imported in 2021. Russia made up 45% of the EU’s natural gas import that year, followed by Norway at 24%, Algeria 13%, US 7% and Qatar 5%. Russia also accounted for 27% of oil imports and 46% of coal imports.3 None of the EU member states are energy self-sufficient. Estonia, Romania and Sweden are the least reliant on imports at 10.5%, 28.2% and 33.5% respectively. In terms of gas consumption, Germany is the largest accounting for 17% of Europe’s total, followed by the UK at 15%, Italy 14%, France 8% and Spain 7%. The share of Russian gas within this, however, paints a different picture: Germany takes 65% of its gas from Russia, Italy 30%, France 19%, and Spain and the UK 10%.4

What about storage levels? According to the Germany energy regulator, Bundesnetzagentur (BNetzA), storage levels in Germany as at 1 July were close to 70%5, which is within range for the time of year based on historic trends. But storage is not being filled while Nord Stream 1 is shut. If volumes resume at 40%, based on current storage levels, the situation is less critical. However, it is widely expected among industry experts and politicians that Russia will continue to disrupt gas supply to Europe. Outside Germany, experts indicate that Italy is relatively well positioned for this winter as gas imports from Algeria ramp up6; in the Netherlands, the country’s gas transmission owner/operator Gasunie stated on 14 July that in the event of a cut to Russian gas suppliers to Europe for a year, there will be no gas shortage in the Netherlands next winter provided numerous conditions, observations and measures are met related to domestic storage, coal-generation capacity and export capacity7.

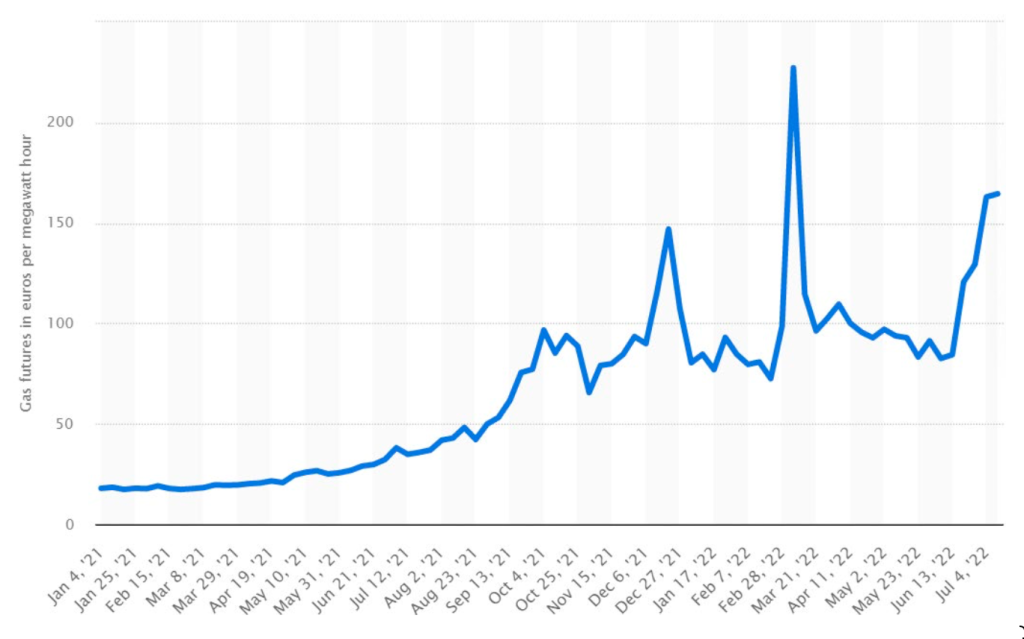

What are gas prices doing now? It is worth remembering price increases started before the war, in Q4 2021. Reasons included market design, the behaviour of some market players and, to a certain extent, a pick-up in demand from China as shutdowns eased. Price behaviour now, however, is solely attributed to news over the reduction of Russian flows (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1: Dutch TTF weekly gas futures Jan 21 to July 21 (EUR/ MWh)

Source: Statista, July 2022

Figure 2: National Balancing Point (UK) £/therm

Source: Bloomberg, July 2022

How does Germany’s energy warning system work? Germany has a three-stage supply warning system. On 30 March it triggered Level 1, an Early Warning Phase, indicating an absence or reduction of gas flows at physical entry points. This is a monitoring stage with no state intervention or real impact. On 22 June it imposed Level 2, the Alarm Phase. At this stage, the domestic market is still able to cope with interruptions without state support, but the state requests “solidarity” from EU member states to help with gas or energy supplies in the event of a shortage. Level 3 denotes an Emergency Phase requiring the state to take over the supply of gas from utilities firms and other energy players. BNetzA becomes the national coordinator, taking on the statutory duty of distributing and allocating gas resources. Demand-side management will be activated and “force majeure” clauses in contracts suspended.

What would occur if the Emergency Phase is imposed? Germany will need to curtail domestic gas consumption this winter if flows do not resume. Curtailment is by instruction and monitoring, followed by penalties if instructions are not followed. It will be very difficult to decide which industry should be curtailed first. A politically palatable situation might be that a pragmatic and non-discriminatory system will be followed, ie all users will be asked to reduce usage by a similar proportion. No politician wants to decide who gets cut off and which supply chain and employee group suffers the most as a result. The BNetzA has made two attempts to survey large energy users to determine a priority list, but all industrials are calling themselves critical. It is in the midst of a third attempt. What is clear is that households and hospitals will be kept secure8.

Is this an EU-wide problem? Potentially, and the request for solidarity among member states will be highly controversial. It will be difficult to shut down industry in one country while its neighbour might continue supporting its own industry rather than sharing gas with neighbours. Gasunie has already made it clear it will cap the level of gas supplied to Germany to preserve domestic security in certain circumstances.

After Uniper, could another big player fail? As Nord Stream 1 flows were curtailed before scheduled maintenance, importers were forced to meet supply obligations by buying gas on the wholesale market. The result being increased liquidity needs. The German government has already earmarked €15 billion of liquidity available at state-owned investment bank KfW for such purposes, with more possible. It has not yet triggered Section 24, which would allow this increased cost to be passed on to end-users. Currently, a bailout of critical energy providers is seen by the German government as preferable to end-user pai. Passing on the costs would, however, result in some demand destruction, which could in turn soften the full blow of Level 3.

What about LNG? At present, there 29 liquefied natural gas (LNG) import terminals in Europe, the bulk in Spain, France, Turkey and Italy. Six are under construction, and 26 more are planned, of which four are in Germany, but these will not be operational in time for winter9. Spain currently does not export its gas to other EU member states. It will be difficult for Europe to compete with Asia on pricing alone in our view, given the size of demand from Asia relative to Europe10.

Will Russia switch off Nord Stream 1 this winter? It is difficult to predict, but it is very likely that Russia will seek to maintain uncertainty around flows into Europe into 2023. It is therefore unlikely that Nord Stream 1 flows will be returned to normal after 21 July, or even back to the lower levels seen in June. Russia has already cut off supplies to buyers in Bulgaria, Denmark, Finland, Poland and the Netherlands11, mainly over the Kremlin’s new payment terms. Europe is, however, a key market for Russia – according to the US’s Energy Information Administration, just under three-quarters of all Russian natural gas exports went to Europe in 202112. There are limited routes for Russia to divert this gas to Asia, but for now high gas prices are offsetting the impact of lower export volumes.

What is a “defensive” European utility now? To avoid exposure to risks from gas disruption, we view a number of sectors as relatively defensive: the regulated UK Water sector as well as regulated electricity transmission and distribution network owners and operators across Europe and the UK. As opposed to gas distribution, gas transmission networks are crucial for LNG growth, in particular new LNG terminals, securing alternative cross-border supplies, maintaining connections to industrial sites and, in future, hydrogen transport13.